The Poverty Advantage: Why Kids From the Ghetto Get 10x More Touches Than America’s Future Prospects

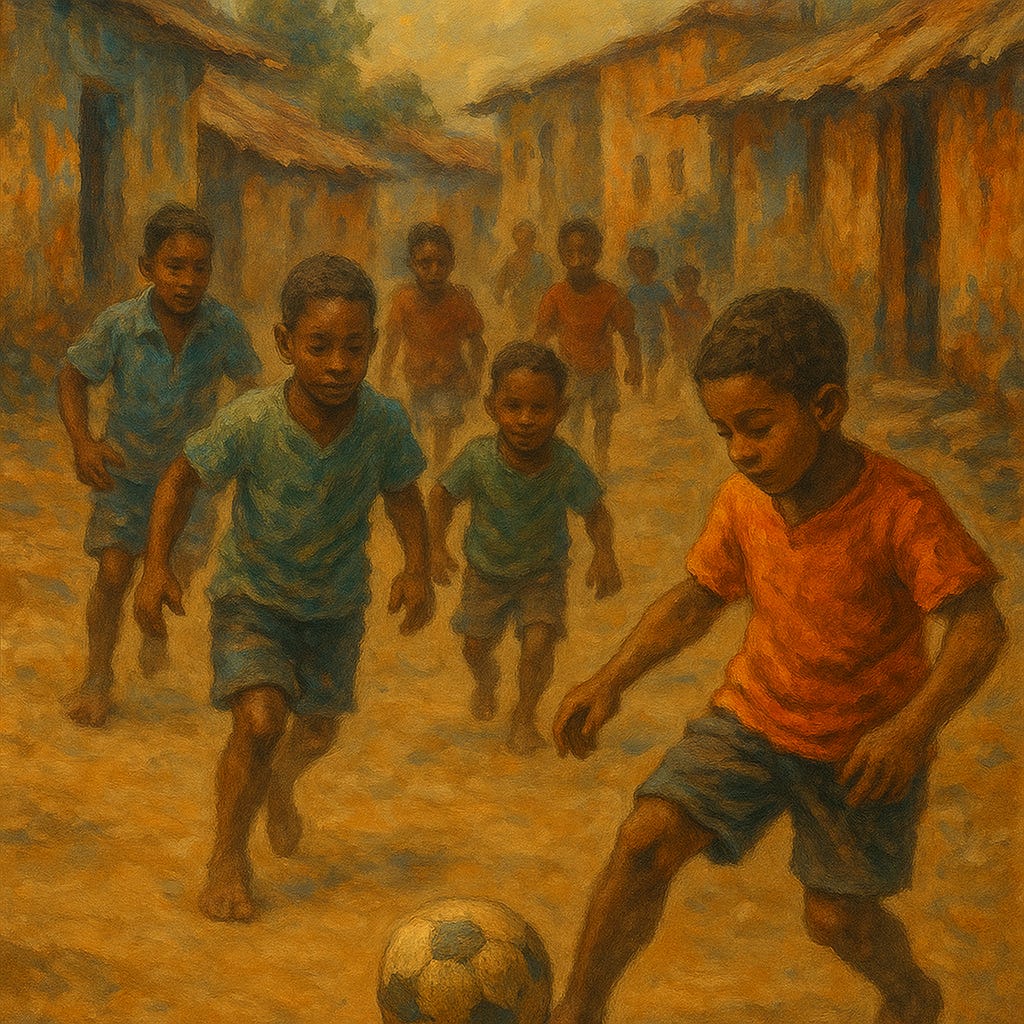

In the alleys of Lagos, the favelas of Rio, and the banlieues of Paris, a barefoot kid is racking up touches that will one day turn into contracts. No cones. No coaches. No parents filming from the sideline. Just rhythm, chaos, and survival.

He’ll touch that ball a thousand times today.

The American kid—whose parents spend $10,000 a year on club fees—will touch it forty.

The Science of Touches

Every elite player’s foundation is built on repetition. Touches per day, multiplied over years, become instinct. The data is simple: if one player touches the ball 2,000 times a day and another touches it 200, the gap by age 15 isn’t additive—it’s exponential. One develops creativity; the other develops compliance.

In the U.S., “development” often looks like a 45-minute car ride, a 90-minute practice, and 15 touches in a rotation-based drill while a coach talks. It’s efficient for the adults, not the kids.

Meanwhile, the kid in the street is in a laboratory of chaos. Every bounce is unpredictable, every opponent is older, faster, stronger. There’s no structure—just survival instincts and muscle memory forming in real time. Over years, those touches accumulate into what we later call flair.

The Over-Coached Culture

America has professionalized childhood. Parents mean well—they want opportunity, exposure, scholarships—but they’ve built an ecosystem that rewards control over creativity. Youth sports have become a business model, not a development model.

Coaches are incentivized to over-structure sessions. Drills look sharp for Instagram but lack spontaneity. A player’s freedom to experiment is often mistaken for undiscipline. And because every minute of “training” is adult-managed, kids lose the one thing global footballers never lack—ownership of their game.

The irony? The world’s best players grew up outside of control. Their environment taught them improvisation. They learned rhythm before tactics, movement before mechanics, courage before curriculum.

The Economics of Freedom

Talent doesn’t emerge from comfort—it emerges from necessity. The reason scouts comb the poorest neighborhoods on earth isn’t charity—it’s efficiency. Poverty creates volume. Volume creates touch. Touch creates talent.

In purely economic terms, the American model misallocates resources. We invest heavily in access but not in hours. The richest families in youth sports have effectively priced their kids out of organic development. The poorer kids, playing endlessly without instruction, are operating on a higher frequency.

Every time a kid in the favela or on a dusty pitch in Accra touches the ball, he’s compounding skill like interest. By the time the American kid arrives at practice, he’s already behind—before the whistle even blows.

The Cultural Equation

Football culture in America is a reflection of the broader society: structured, time-boxed, optimized. But football itself thrives on the opposite. It’s improvisational art. It’s about rhythm, reaction, and chaos management.

The global game still belongs to the kid who plays without supervision. The question for America isn’t whether it can pay for better coaching—it’s whether it can unlearn control.

Because at the end of the day, football doesn’t care about zip codes, tuition, or carpool miles. It only cares about touches.

And right now, the world’s poorest kids are touching the ball ten times more than America’s richest.