Left on the Sidelines

The Exclusion of Black Athletes from U.S. Soccer Development

American soccer has a diversity problem. On playgrounds in cities like Atlanta, Baltimore, and Los Angeles, countless Black children possess the speed, creativity, and athleticism to thrive in “the beautiful game.” Yet few ever make it into elite soccer pipelines. Instead, systemic barriers – historical neglect, economic hurdles, and cultural dynamics – have kept Black American athletes largely on the sidelines of U.S. soccer. This report examines how those forces have led to persistently low Black participation in soccer, especially compared to sports like football, basketball, and track. It also explores the timelines and access points of youth development in different sports, quantifies the talent gap with demographic data, and analyzes how pay-to-play models and elite academies like MLS NEXT often fail Black communities. Importantly, we highlight voices of change – the nonprofits, grassroots academies, pro clubs, and community leaders working to rewrite soccer’s story – and present expert insights and policy ideas to level the playing field.

A Legacy of Barriers: Historical, Economic, and Cultural Factors

For much of the 20th century, soccer in the United States grew apart from many Black communities. Unlike football and basketball, which were embraced in urban schools and playgrounds, soccer’s American boom in the 1990s largely unfolded in suburbs and affluent enclaves . Early on, U.S. soccer’s structure simply did not reach many African American neighborhoods. Doug Andreassen, former chair of US Soccer’s diversity task force, noted back in 2016 that thousands of gifted athletes in mostly Black and Latino neighborhoods were “getting left behind” by a system that rewarded wealth and geography . While the world’s game flourished in the favelas of Brazil and the townships of Africa, in the U.S. it became “determined by how many zeroes a parent can write in their checkbook,” Andreassen observed . Soccer was touted as the great democratic sport – “a ball and any patch of grass is all you need” – but in America, that ideal gave way to paywalls and exclusive clubs. The result? A generation of Black youth mostly alienated from soccer, with few role models in the sport and fewer opportunities to play at a high level.

Economic factors have been paramount. Unlike school-based sports, competitive youth soccer in the U.S. runs on a costly private club system. Families often must shell out thousands of dollars per year in club fees, travel expenses, and equipment . “It’s a very inexpensive sport, and the fact that we’ve made youth soccer a business is detrimental,” lamented U.S. star Alex Morgan . In Southern California, top clubs charge anywhere from $1,000 up to $10,000 annually per child . Nationally, a 2018 survey found over 70% of kids in organized soccer came from households earning above $50,000 a year – and one-third from $100,000+ homes . By comparison, the median Black household income was around $41,500 . The math is simple: pay-to-play pricing excludes a huge segment of Black families. Youth soccer today skews heavily white and middle-class, an imbalance even insiders acknowledge. “I do think it is exclusionary to a degree…you can’t have all these barriers to entry,” said former U.S. Men’s National Team star Cobi Jones . Jones and others have warned that promising Black players are being priced out of the sport long before they can be discovered.

Cultural perceptions have also played a role. For decades, soccer lacked a strong foothold in African American culture, which has been more closely tied to legacy sports like football, basketball, and track. Black kids did not grow up seeing many soccer heroes who looked like them. In 2015, the Women’s World Cup champions were almost entirely white , and even on the men’s side, many of the few non-white U.S. national team players were foreign-born or of immigrant heritage . This absence of representation fed a self-perpetuating cycle: soccer wasn’t seen as a “Black sport,” so fewer Black youth tried it – and those who did often felt like outsiders. “Soccer has not always been the most welcoming,” says former pro player and broadcaster Renee Washington, noting that Black girls in particular seldom saw themselves on the pitch . One young Black woman recalled being “always the only Black girl” on her club teams and feeling judged or out of place . Such experiences highlight the climate of exclusion that can discourage Black participation.

It’s important to stress that these barriers are systemic, not the result of any lack of interest or ability among Black athletes. In fact, where opportunities exist, Black talent has shined. Historically Black colleges like Howard University produced soccer champions in the 1970s. And in recent decades, Black stars from abroad – from Didier Drogba to Kylian Mbappé – have shown the heights Black athletes can reach in this sport. But in the U.S., soccer’s structural gatekeeping has kept the vast majority of African American athletes on the outside looking in. As Andreassen put it bluntly, “The system is not working for the underserved community… It’s working for the white kids.” .

Divergent Paths: Soccer vs. Football, Basketball, and Track

To understand why Black athletes flock to certain sports over soccer, one must compare the youth development pathways and payoffs of each. American football and basketball have long been integrated into public schools and inner-city recreation, creating a natural pipeline for Black talent. A child can pick up a basketball at the local park or join a school football team with virtually no cost. Equipment, coaching, and competition are provided through school programs funded by tax dollars. By high school, standout players in those sports are scouted for college scholarships. “Basketball and football have made peace with African Americans — with full college scholarships and lavish compensation at the pro level,” veteran sportswriter William C. Rhoden observes . In other words, these sports actively recruit Black youth by offering clear paths to education and professional earnings.

Soccer’s path is starkly different. Timeline and early specialization set it apart: elite soccer development often begins at 5 or 6 years old in structured environments. By the time a player is a teenager, the top opportunities – like academy slots or Olympic Development Program teams – may have already been allocated to those who’ve been in the pipeline for years. By contrast, football players often don’t play until middle school or later, and many track athletes don’t discover their gift for sprinting or jumping until high school. This later start in other sports means a talented 14-year-old who’s never played organized basketball can still be groomed into a Division I prospect, but a 14-year-old soccer newbie will have a much harder time catching up to peers with a decade of training. Soccer’s early start and year-round commitment leave less room for late bloomers – which disproportionately hurts youth from communities without robust early soccer programs (often Black and low-income areas).

Access points also differ greatly. In football and basketball, school teams and city leagues serve as free entryways. A kid in Baltimore or Detroit can make the high school basketball team without ever having paid club fees; a strong season can earn them an invite to an AAU tournament or a college showcase. In track and field, any student can join the spring track team for free and potentially uncover world-class talent in sprints or jumps. These traditional sports essentially subsidize development – the public school system and nonprofit youth leagues shoulder the costs, ensuring that ability (not family income) drives advancement, at least through the high school level.

Soccer, however, has relied on an outside-club model. School soccer teams exist but are often secondary in college recruiting to club teams. Top U.S. soccer prospects typically funnel through travel clubs or professional academies that are pay-to-play (unless affiliated with a pro club). That means a kid who cannot afford club dues or who doesn’t live near an academy is likely invisible to the soccer talent scouts. By contrast, in basketball a phenom at a local playground can get noticed and invited to an AAU team without cost, and in football a dominant high school running back from any district can earn a college scholarship that covers tuition.

Finally, the economic opportunity in each sport influences family decisions. The NFL and NBA are lucrative goals – even a journeyman NFL player earns a substantial salary, and the prospect of a full ride to college or a pro contract can justify intense investment in those sports. For track athletes, the pro earnings are smaller, but many see track as an accessible way to win a college scholarship or as complementary training for other sports. Soccer’s domestic pro league (MLS) historically offered much more modest pay, and only recently have a few American stars begun earning multi-million dollar contracts (often by moving to European leagues). Until very recently, it was hard for parents to envision soccer as yielding the same scholarship and career benefits as basketball or football. “The NFL, NBA – they’re culturally relevant. They dominate the sports landscape,” says Sola Winley, MLS’s diversity chief. Soccer, on the other hand, is still building its reputation and financial rewards in the U.S. . This matters in Black communities where parents and coaches often encourage kids to pursue the sports with the most secure payoff. As one community coach put it: why pour money into youth soccer fees on a slim hope of a partial college scholarship, when a child can run track or play football at school for free and potentially go to college for free?

In sum, Black youth face a friendlier road in other sports – with accessible entry, visible role models, and clearer returns – whereas soccer’s road has been narrow, costly, and uncertain. The next section quantifies just how stark the participation gap has become.

Untapped Talent: Demographics and the Scope of the Gap

One way to measure soccer’s missed potential is to look at who gets to play at various levels. African Americans comprise roughly 13% of the U.S. population , and their athletic achievements in football, basketball, and track suggest a well of talent proportionate to that share. Yet in American soccer, Black athletes are underrepresented at almost every stage of the pipeline – from youth leagues to college rosters to the pros. The data tells a jarring story of untapped talent.

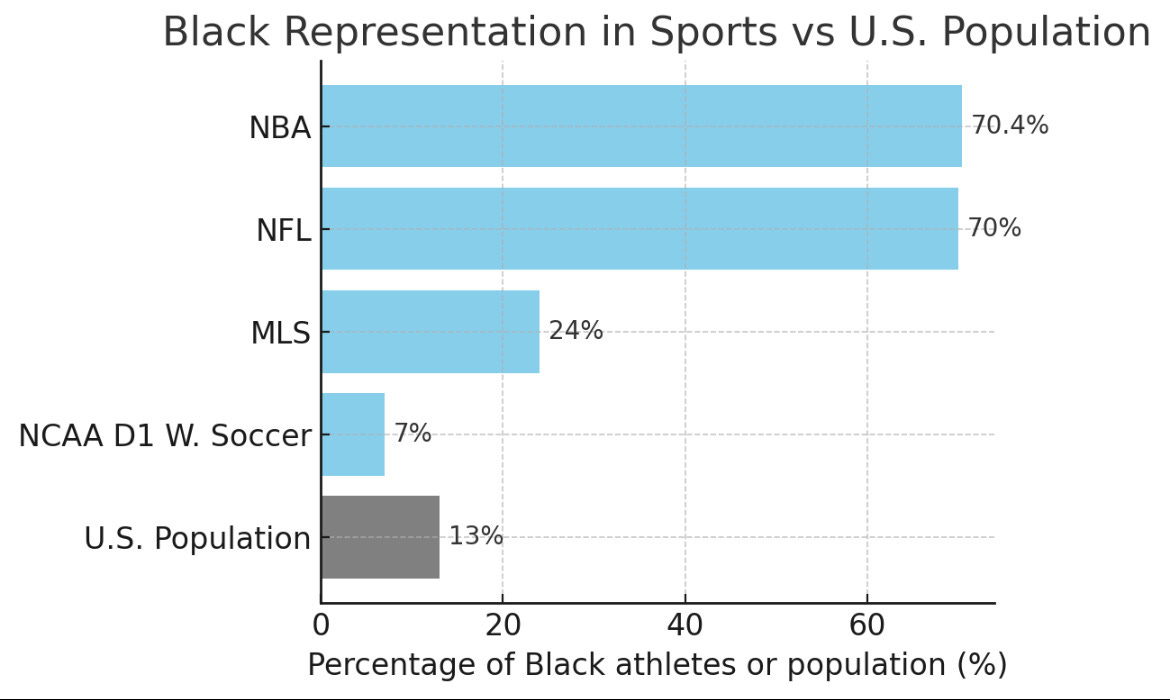

Black representation in soccer remains far below that in other major U.S. sports, despite Black Americans comprising roughly 13% of the population . For instance, around 70% of NFL and NBA players are Black , while only 24% of MLS players are Black and just 7% of Division I women’s soccer players are Black .

At the youth level, precise nationwide data by race is scarce, but available indicators reinforce the gap. According to the Aspen Institute’s Project Play survey, Black youth report playing soccer at lower rates beyond casual pickup compared to some other groups, likely due to access issues. Meanwhile, high school sports participation skews heavily by sport: in many urban schools, football and basketball rosters are majority Black, whereas soccer teams (if the school even has one) often have few Black players. By college, the disparity is glaring. In NCAA Division I men’s soccer, black players historically made up only around 10–15% of athletes (many of them foreign-born Africans or Caribbeans). On the women’s side it’s even smaller: only 7% of D-I women’s soccer players are Black, up from 5% a decade ago . This means roughly 93% of players at the top college level are non-Black, in a sport where Black women like Crystal Dunn and Briana Scurry have proven world-class ability when given the chance.

In the professional ranks, the MLS player pool is about 24% Black – better than at youth levels, but still far below the NFL (≈58–70%) or NBA (≈70%). And notably, a significant number of Black MLS players are of African or Caribbean descent, indicating that U.S.-born Black players are still not coming through in large numbers. The U.S. Men’s National Team (USMNT) in recent years has featured several prominent Black players (such as Tim Howard, Jozy Altidore, DaMarcus Beasley, and more recently Tyler Adams and Tim Weah), yet the overall pipeline remains thin. Many Black USMNT players have backgrounds outside traditional U.S. youth soccer – some having immigrant parents who taught them the game or unique routes into academies. The U.S. Women’s National Team (USWNT) has historically had even fewer Black athletes; as of 2022 only three Black women were on the national roster , and stars like Crystal Dunn have spoken about feeling like an anomaly in youth soccer. By contrast, look at track and field: at the 2021 U.S. Olympic Trials, roughly half of the top 100m sprinters and a large share of finalists in jumping events were Black, reflecting near proportional representation.

These numbers underscore a sobering truth: America is missing a huge pool of athletic talent in soccer. If African American kids participated in soccer at rates similar to football or basketball, the sport would have hundreds of thousands more players – and likely many more elite standouts. One analysis in The Guardian bluntly asked why the U.S. hasn’t “unlocked this talent base” and noted that a quarter-century into soccer’s rise, urban Black athletes still aren’t embracing the sport . Interest isn’t the core problem – many Black youths do enjoy soccer casually – rather, it’s the lack of organized pathways. As MLS executive Sola Winley points out, “A kid from a poor Black community has not yet been exposed to soccer in any sort of substantive or intentional way. It’s the last group on the globe that hasn’t been exposed to this sport” . The talent is there, waiting to be cultivated. The next section examines why the prevailing system struggles to reach that talent.

The Pay-to-Play Pipeline: How U.S. Soccer Leaves Black Communities Behind

At the heart of U.S. soccer’s developmental woes is its pay-to-play model – a system that effectively puts up a toll booth at the entrance of the sport. In theory, soccer should be the most accessible of games (a ball and a patch of dirt will do). In practice, American youth soccer has become “something akin to polo, a sport for the very rich,” as one coach quipped in frustration . Unlike youth basketball or football, where participation is generally free, playing competitive soccer in the U.S. often requires significant money up front.

Black families are disproportionately affected by this paywall. On average, Black households have lower incomes and less generational wealth due to systemic economic inequalities, so steep soccer fees pose a heavier burden. A parent choosing sports for their child might balk at a $2,000/year soccer club fee when sports like football, basketball, or track cost little to nothing. As Sola Winley notes, “It can cost $3,000 on average to play travel soccer, and that’s not including the cost of travel” . For many working-class and Black families, that sum is prohibitive. While some clubs offer need-based scholarships, “charity is not a sustainable strategy for inclusion,” Winley emphasizes . The reliance on a pay-for-play structure means that far too often, talented kids are shut out simply because their parents can’t pay. “You don’t want a situation where a good player can’t go on to higher levels because they can’t afford the fees,” Cobi Jones says, yet that is exactly the situation today .

Consider the elite youth clubs and tournaments that feed college and pro scouts. Many are expensive showcases in far-flung suburbs or out-of-state venues. A kid from inner-city Chicago or Atlanta might have the skill to dominate, but if they’re not on a travel team, they won’t even know about the showcase – and can’t afford to get there regardless. Former U.S. star DaMarcus Beasley, who grew up in a modest neighborhood, noted that without a free academy opportunity, he wouldn’t have made it. In many Black communities, there is no local club at all, or it’s understaffed and underfunded. By contrast, suburbs often boast multiple well-equipped clubs. This geographic inequality often maps onto race: soccer’s infrastructure has flourished in predominantly white, affluent areas, and withered in low-income Black areas . One Black player from Kansas City recalled that all the competitive clubs were 30–40 minutes away in wealthy suburbs, and “the areas these clubs are in are nice…with most of the population being white” . That left her often as the only Black girl on the team, feeling isolated despite her passion.

The rise of MLS NEXT and professional academies in recent years was supposed to mitigate pay-to-play by providing free, high-level training programs. Indeed, every MLS pro club now runs a youth academy that is cost-free for selected players. However, these academies have limited slots and tend to recruit from the existing club soccer system. In practice, a talented kid usually must first get noticed in pay-to-play leagues before being scouted by an academy. For instance, a standout 12-year-old in a local recreational league might have no pathway to an MLS academy unless someone sponsors them into a travel team that competes against academy teams. MLS NEXT (the academy league) has also absorbed many non-MLS clubs which still charge fees to participants. So while a portion of elite players pay nothing, the vast majority of youth in MLS NEXT came up through pay-to-play clubs to earn their spot. The funnel narrows early and misses those who couldn’t pay to enter it.

The cost barrier doesn’t end at youth level either. Even after youth soccer, pursuing the sport often means college soccer (which offers few full scholarships – men’s soccer, for example, is an “equivalency” sport with partial scholarships, unlike full-ride sports such as football/basketball) or lower-division pro play for very low salaries. For many Black athletes, the prospect of grinding through minor-league soccer for $20,000 a year is far less appealing than other avenues they could pursue. This is why soccer hemorrhages many top athletes to other sports by their late teens – even those who love soccer may switch to sports that offer more support and stability. “Even the young Black athlete who comes from a middle- or upper-middle-class family gravitates to football and basketball,” Winley observes, “How will soccer bring these athletes into its universe?” .

Critics argue that U.S. Soccer and the youth soccer establishment have been slow to reform the pay-to-play system that they financially benefit from. Youth clubs and tournament organizers make money under the status quo, reducing incentive to change. “It’s become very profitable for a lot of organizations,” Cobi Jones notes of pay-to-play, “To be honest, I think it would be difficult to root it out” . Former U.S. international Alexi Lalas has controversially defended pay-to-play as a market-driven outcome, saying “Soccer (like piano lessons) is not an inalienable right. Free soccer costs money. Someone has to pay.” . But that attitude, many contend, ignores the national cost of excluding masses of players. As one Philadelphia coach put it, “If it costs $1,500, 2-grand a year for a 12-year-old to play soccer, well that’s just not feasible for a large number of people” . Those are the kids – often Black, often in inner cities – that U.S. soccer is losing.

In summary, the pay-to-play pipeline acts as a filter that strains out many Black athletes long before selection on merit could even occur. It’s a structural problem – not a lack of interest or ability – that explains why relatively few African Americans reach elite soccer. The good news is that across the country, innovators at the grassroots level are striving to break this mold. The next section highlights some of the most promising efforts to bring soccer to underserved Black communities without the usual barriers.

Grassroots to Pro: Bringing Soccer to Black Communities

In the face of systemic obstacles, a growing movement of organizations and individuals is working to make soccer accessible and inclusive for Black youth. These efforts span from small nonprofits building fields in urban neighborhoods, to MLS clubs forging community partnerships, to independent academies proving that if you invest in Black communities, talent will emerge. Below, we spotlight several case studies and leaders driving change:

Soccer in the Streets (Atlanta, GA): In Atlanta – a city that’s been dubbed the “Black Soccer Capital of America” due to its burgeoning Black fanbase and player pool – the nonprofit Soccer in the Streets has pioneered an innovative program called Station Soccer. In 2016, they opened the world’s first soccer field inside a public transit station (at Five Points MARTA station) to eliminate the transportation barrier for urban youth . Kids from Atlanta’s Westside neighborhoods can now hop on a train after school and find free coaching and league play literally at the station. “Our youth can engage in programs where transportation may have been a limiting factor,” explains Lauren Desmond, Soccer in the Streets’ director of coaching . With support from Atlanta United FC and city officials, Station Soccer has expanded to multiple transit stops, creating a network of mini-pitches across the city. “By building communities around transit, we are integrating youth and adults and giving access to all,” says board member Sanjay Patel . Over 4,000 kids – many from predominantly Black neighborhoods – have participated in these free programs, gaining quality training that once was out of reach. Atlanta’s model shows how deliberate infrastructure changes (like bringing fields to where the kids are) can open soccer to a new population. The city’s embrace of soccer – from packed Atlanta United games with diverse crowds, to rappers sporting the team’s gear – also illustrates how quickly cultural perception can shift when a community is included.

U.S. Soccer Foundation Mini-Pitches (Multiple Cities): On a national scale, the U.S. Soccer Foundation (the charitable arm of U.S. Soccer) has invested in building hundreds of mini-pitches in urban areas to provide safe, free play spaces. For example, in Baltimore, a city with a rich Black sports heritage but limited soccer infrastructure, the Foundation partnered with local parks to install small soccer courts in diverse neighborhoods . In historically Black areas like West Baltimore, these brightly colored mini-pitches have sprung up in rec centers and schoolyards, sparking pickup games among kids who previously had nowhere to play soccer. Baltimore’s recreation department also launched free youth soccer clinics at 44 recreation centers, ensuring the sport is offered alongside basketball and football for any child who’s interested . The impact is two-fold: not only do the kids get to play, but seeing soccer become part of the neighborhood landscape (courts full of young Black and Latino players) starts to normalize the sport in communities that once felt excluded. Similar mini-pitch initiatives have taken root in cities from Los Angeles to Newark, *“providing these communities the opportunity to play soccer right in their neighborhoods” . It’s a grassroots strategy to literally carve out space for soccer in places it was absent.

Community Clubs & Academies: In some cities, local leaders have formed independent clubs specifically to serve Black and underserved youth. In Washington D.C., for instance, the Open Goal Project offers free high-level training to kids from low-income wards, helping them earn scholarships to private schools and college programs. In Philadelphia, the Anderson Monarchs, a club based in a historically Black South Philly neighborhood, famously trained a young goalie named Zack Steffen – who went on to play for the USMNT – on scholarship. These community-rooted clubs often operate on shoestring budgets and donations, yet they produce remarkable success stories when given support. One standout example abroad is Lambeth Tigers in London, UK. While not in the U.S., Lambeth Tigers is instructive as a case study in a similar context of underrepresented groups. Based in a predominantly Black area of South London, this nonprofit club offers nearly free football to local kids. In just five years, Lambeth Tigers saw over 75 boys signed into professional academies – a testament to the wealth of talent that can be unlocked with the right outreach. They emphasize providing quality coaching in a “structured, disciplined and caring environment” for kids who might be overlooked by traditional systems . The club’s success drew attention from stars like Jadon Sancho, who partnered with Nike to build the team a new turf pitch and lend his name in support . Lambeth’s model – identifying talent in one of the world’s most deprived communities and nurturing it to elite levels – is precisely what many advocates envision for U.S. cities if soccer investment flows there.

MLS Club Initiatives: Some professional teams are recognizing that their future fan base and player roster depend on connecting with communities of color now. For example, LAFC (Los Angeles) and DC United have programs to provide free clinics in inner-city schools and have hired community development staff to scout in Black and Latino neighborhoods. The Atlanta United Foundation, as noted, has heavily funded Soccer in the Streets and school programs in Atlanta’s Westside . In Chicago, Fire FC runs the P.L.A.Y.S. program (Participate, Learn, Achieve, Youth Soccer) in public schools with majority Black student bodies. And at the national level, MLS hired Sola Winley as its first Chief Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Officer in 2021 . Winley’s mandate includes “widening access to youth participation” and “removing barriers to participation” . While it’s too early to judge outcomes, the fact that MLS created a high-ranking role focused on diversity is a positive sign. Winley has spoken about intentionally introducing soccer to Black communities, noting that unlike Latino or immigrant groups, many Black American kids still haven’t had someone simply invite them into the game .

Black Players and Coaches as Mentors: Another encouraging development is the rise of Black-led mentorship and training programs. Former U.S. players like Tony Sanneh (whose Sanneh Foundation runs free soccer camps in Minneapolis’s African American neighborhoods) and Kim Crabbe (the first Black woman on the USWNT, who coaches girls of color in the South) are paying it forward. There’s also the Black Soccer Coaches Association, which supports Black coaches to rise in the ranks, and community figures like Justin Reid – an NFL player who in 2022 donated funds to start a soccer program at his father’s alma mater, Prairie View A&M (an HBCU). Each of these efforts, big or small, chips away at the notion that soccer “isn’t for” Black kids. They send the message: you belong on this field.

Together, these grassroots and institutional efforts are lighting new pathways into soccer for African American youth. They show that the appetite is there – when the costs are removed and outreach is genuine, Black kids flock to the game. From the 250+ children in Atlanta’s new station-soccer after-school programs to the young girls filling up free soccer clinics in Watts and Harlem, we are seeing the beginnings of a more inclusive soccer culture. But scaling these successes into a national norm will require concerted action and changes at the highest levels of American soccer. In the final section, we turn to expert perspectives on what more is needed to truly level the playing field.

Leveling the Playing Field: Expert Insights and Policy Recommendations

Bringing long-term equity to U.S. soccer will demand systemic change, not just isolated programs. As Sola Winley stated, “We have to figure out a way to have systemic change. The answer to that? I don’t know what that is yet.” . While there’s no single silver bullet, experts and advocates have proposed a range of solutions to address structural inequities. Drawing on their insights, this report presents the following key recommendations:

1. Reinvent the Development Model – Make Youth Soccer Affordable (or Free) for All. The pay-to-play paywall must come down if soccer is to tap into the full American talent pool. U.S. Soccer, MLS, and youth organizations should work towards a model where cost is not a barrier to entry. This could include expanding the number of fully funded academy programs (not only via MLS clubs, but also through community-based academies funded by grants or endowments), increasing scholarships at existing clubs, and supporting low-cost recreational leagues in minority communities. The U.S. Soccer Federation (USSF), flush with revenues from the 2026 World Cup, can subsidize grassroots clubs and mandate diversity outreach as a condition of its funding. Learning from global examples, U.S. Soccer might partner with local governments to designate soccer as part of public youth sports offerings. If American youth soccer looked more like, say, France’s system – where regional training centers identify and train kids at no cost – we’d remove a massive barrier. “Free soccer isn’t actually free – someone has to pay – so who will pay for all this free soccer?” asked Alexi Lalas skeptically . The answer should be: the stakeholders who benefit from a thriving U.S. soccer talent pool (leagues, sponsors, federations) must invest at the base so families don’t have to. In the long run, this investment pays for itself by producing more elite players, a stronger national team, and a larger fan base.

2. Build Bridges Between Schools and Clubs. To catch more Black athletes, soccer needs to exist where they spend their days – in schools and community centers. One idea is for USSF to collaborate with state high school athletic associations to elevate high school soccer in urban districts. That could mean providing better coaching and facilities to inner-city school teams and scouting those games aggressively for talent. Instead of dismissing high school soccer, academies could partner with schools to create hybrid models (allowing academy training but school team play for broader exposure). Additionally, after-school programs should integrate soccer alongside basketball and football. Programs like Soccer in the Streets show that bringing soccer to schools (e.g. in Atlanta public elementary schools ) can draw hundreds of new players. By forging partnerships, a promising player who shines in a school league can be referred (free of charge) to a competitive club or development academy. This approach uses existing public sports infrastructure to widen the funnel of talent identification.

3. Prioritize Diversity in Coaching, Scouting, and Leadership. Representation matters not just on the field but among those who make decisions in soccer. Increasing the number of Black coaches, scouts, and club administrators can help change recruitment patterns and make Black youth feel more welcome. MLS’s hiring of more Black executives and coaches is a start . But we also need coaches at the grassroots – in peewee leagues, park districts, travel teams – who come from the communities they serve. Black coaches can be role models and can better spot potential in kids who might be overlooked by others. As one advocate said, “If you don’t have diverse coaches, you won’t have diverse players – it’s a circle”. USSF’s coaching education should actively recruit and mentor coaches of color, offering scholarships for licensing courses. At the same time, scouting networks should be rebuilt to include urban areas: hiring scouts to attend inner-city tournaments, futsal leagues, even flag football games (where you might find a great athlete who could convert to soccer). One novel idea is a “Rooney Rule” for youth soccer scouting – requiring academies to evaluate talent from a variety of socioeconomic backgrounds.

4. Leverage HBCUs and Community Colleges to grow the game. Historically Black Colleges and Universities largely do not have men’s soccer programs (in part due to resource constraints and NCAA dynamics). This is a missed opportunity to engage more Black athletes in the sport during college. Initiatives like the one at Morris Brown College, which is partnering to launch its first ever soccer team , should be supported and replicated. If HBCUs added soccer (with help from grants or partnerships with pro teams for coaching expertise), they could become hubs for developing Black players who didn’t go through the elite pipeline. Similarly, community colleges in urban areas could offer soccer scholarships and serve as a bridge for late-developing players. Strengthening these alternative pathways ensures that even if a player is a “soccer late bloomer,” they have a route to continue and potentially turn pro. It also increases visibility of the sport on Black college campuses, further intertwining soccer with Black communities.

5. Change the Narrative and Marketing of Soccer in Black Media and Culture. Beyond structural fixes, there’s a cultural shift needed. Soccer has to be seen as cool, welcoming, and ours in Black America. The success of Atlanta shows how this can happen: hip-hop artists, Black celebrities, and a young urban fan culture made soccer matches the place to be. MLS and U.S. Soccer can intentionally market to Black audiences – featuring Black players in commercials, partnering with Black-owned media, inviting local go-go bands or step teams to perform at halftime, etc. Representation in branding tells kids “you belong.” When a young athlete sees an MLS All-Star Game celebrating HBCU players or watches USMNT stars like Weston McKennie draped in a Pan-African flag, it sends a powerful signal. Moreover, sharing the stories of Black soccer heroes – past and present – can inspire the next generation. How many kids know that the U.S. once had an all-Black team (Howard University) win the NCAA championship, or that a Black American (Cobi Jones) is the all-time caps leader for the USMNT? These narratives need amplification. In short, soccer must actively invite Black America in, both on the field and in the stands.

6. Sustain and Scale Grassroots Successes. Finally, the promising programs highlighted earlier need to be not just sustained but scaled up massively. That means major funding. Corporate sponsors and foundations should view programs like Soccer in the Streets, Detroit’s Futbolero initiative, or Oakland’s Street Soccer USA courts as social investments worthy of grant money. Imagine if every major metro area had a Station Soccer network like Atlanta’s, or if every large public high school without a soccer field got a donated mini-pitch from the U.S. Soccer Foundation. Policies could support this: city governments could allocate unused lots or old tennis courts to be converted to futsal courts. Parks departments could include soccer in free summer sports camps. In many cases, it’s about reallocating resources – for instance, using some of the revenue from high school football championships to fund a new soccer league. When scaling, it’s crucial to involve the community in leadership to keep efforts culturally informed and ensure local buy-in.

Implementing these changes will require coordination between many stakeholders – U.S. Soccer, MLS, schools, nonprofits, and community leaders. There are encouraging signs: the conversation around diversity in soccer is louder than ever, especially after the U.S. women’s early exit in the 2023 World Cup raised questions about whether the pay-to-play system is yielding enough talent . Soccer executives are publicly acknowledging the problem and looking for answers. As one MLS official said, “If we continue to only appeal to kids whose parents can pay, we’ll never be a true soccer nation.” The energy of the World Cup coming to American soil in 2026 also provides a perfect catalyst to launch legacy programs focused on inclusive development.

Conclusion: From Exclusion to Empowerment

For too long, the American soccer dream has been accessible to only a privileged slice of the population. The exclusion of African American athletes from U.S. soccer is not just a story of individual missed opportunities, but a collective failing – a loss of potential greatness for U.S. soccer as a whole. Unlocking the full talent of our country means ensuring the next Pelé or Megan Rapinoe could just as likely come from inner-city Cleveland or rural Mississippi as from any suburb. It means that a Black child watching the World Cup can see a pathway for themselves in the sport beyond just admiration.

The challenges are deeply rooted in history and structure, but the winds are shifting. On concrete courts in Newark and grassy lots in Compton, you can now find kids dribbling soccer balls where once there were none. Nonprofits, educators, and coaches of all colors are working hand-in-hand with communities to make the game truly the people’s game. The examples of progress – from Atlanta’s vibrant youth scene to Lambeth’s prodigies – prove that when barriers are removed, Black excellence in soccer follows naturally.

Achieving equity in soccer development is not a token gesture; it is a competitive imperative and a moral one. The United States’ greatest sporting strength has always been its diversity – the melting pot that produced Jesse Owens and Jackie Robinson also produced Serena Williams and LeBron James. It is time for soccer to fully join that legacy. By breaking down systemic barriers and proactively opening doors, U.S. soccer can empower a generation of African American players to take the field. And when they do, the sport will be richer – in skill, style, and spirit – for it.

In the words of one hopeful coach, “We used to say: How good would we be if we could just get the kids in the cities? Imagine the day we finally do.” The task now is to make that imagined day a reality. The future of American soccer – faster, stronger, and more inclusive – depends on it.

Sources:

Les Carpenter, The Guardian – “‘It’s only working for the white kids’: American soccer’s diversity problem,” June 2016 .

Ryan Baldi, The Guardian – “‘You can’t have barriers’: is pay-to-play having a corrosive effect on US soccer?” July 2024 .

William C. Rhoden, Andscape – “MLS understands need for more Black US soccer players,” July 2023 .

Aniaya Reed, Northeast News – “The lack of black players in American soccer,” Aug 2022 .

Shara T. Taylor, Philadelphia Sun – “Increasing numbers of women of color in soccer at D-I schools,” July 2024 .

U.S. Soccer Foundation – “Mini-Pitches Add to Soccer Legacy in Baltimore,” 2020 .

Soccer in the Streets – “Station Soccer – Five Points Launch,” Oct 2016 .

Aspen Institute – State of Play 2022 report (youth sports participation data) .

U.S. Census Bureau – QuickFacts (Black population statistics) .

Additional interviews and data via NPR, Yahoo Sports, MLS news, and various local initiatives .