College Football’s Missing Piece: The GM Revolution Nobody Understands

The economics of college football have undergone a structural shift. What was once a model centred on scholarships, fixed rosters, and an academy-style developmental pipeline is now a complex ecosystem of transfers, name/image/likeness (NIL) monetisation, and talent markets. Yet many programmes continue to operate as though the only organisational axis is the head coach. This mismatch creates strategic inefficiencies.

Key Economic Data Points

The average FBS football program’s annual expenses increased from about US$7.5 million in 2003 to over US$22 million by 2018.

Recruiting costs are rising: among public Power Five schools, the average increase in recruiting spend per school was about US$103,000 between cycles.

The NIL market has exploded — one report projects the total NIL market moving from about US$917 million in 2021-22 to US$1.67 billion in 2024-25.

Transfer-portal mobility is dramatically altering roster stability and culture: for example, over 11,900 division I FBS athletes entered the portal in 2022, a ~15% year-over-year increase.

A recent economic study shows NIL deals are functioning like a form of personalised pricing in the college football talent market — altering competitive dynamics.

Implications

These data suggest several shifts:

Rising costs: Budgets are ballooning, meaning programmes need higher returns (wins, bowl appearances, fan engagement) just to break even.

Talent as asset: With NIL and transfer markets, each athlete is increasingly viewed as a tradable/valuable unit, not just a scholarship recipient.

Mobility & volatility: With more transfers and more athlete choice, rosters are less stable, making traditional long-term roster building harder.

Brand and business stakes: NIL and media rights have made the football programme more enterprise-like; donors, collectives, sponsors, and athletes all behave like stakeholders in a business.

Why Traditional Organisational Models Fail

Most college football programmes still centre on the head coach as the sole strategic and operational decision-maker. “Recruiting, player development, culture, donor relations, NIL, transfers” all feed into the head coach’s office. But this model is increasingly sub-optimal.

1. Task complexity and specialisation

When the coach also runs recruiting budgets, NIL negotiations, portal acquisitions, media relations, culture-building, player development, and on-field strategy — you have functional overload. In corporate economics this is akin to expecting a CEO to also be CFO, CMO, and Head of R&D. Specialisation improves efficiency.

2. Asset allocation mismatch

Working with the data above, consider that recruiting spends are high and rising; NIL deals incentivise athletes to view themselves as brands; transfers mean value can shift quickly. Without a dedicated executive whose job is to optimise the athlete portfolio (which athlete we keep, which we add, what NIL exposure we secure, how we balance high-school recruiting vs portal acquisitions), programmes fall behind.

3. Market signalling failure

Athletes, agents, and collectives are now making decisions based not only on the programme’s tradition, location, or coaching staff — but on business value (NIL potential, athlete brand growth, future transfer/exit prospects). Studies show recruits increasingly factor NIL and transfer‐market dynamics into their choices. If your programme lacks a business-savvy front office, the signalling effect is weak.

4. Culture and retention risk

The research on the transfer portal underscores that high player mobility undermines long-term culture building. Coaches interviewed indicated routine use of the portal made it harder to build sustained identity and commitment. A GM who can manage retention strategies, value retention vs acquisition, and integrate business incentives into culture becomes critical — yet many programmes ignore this.

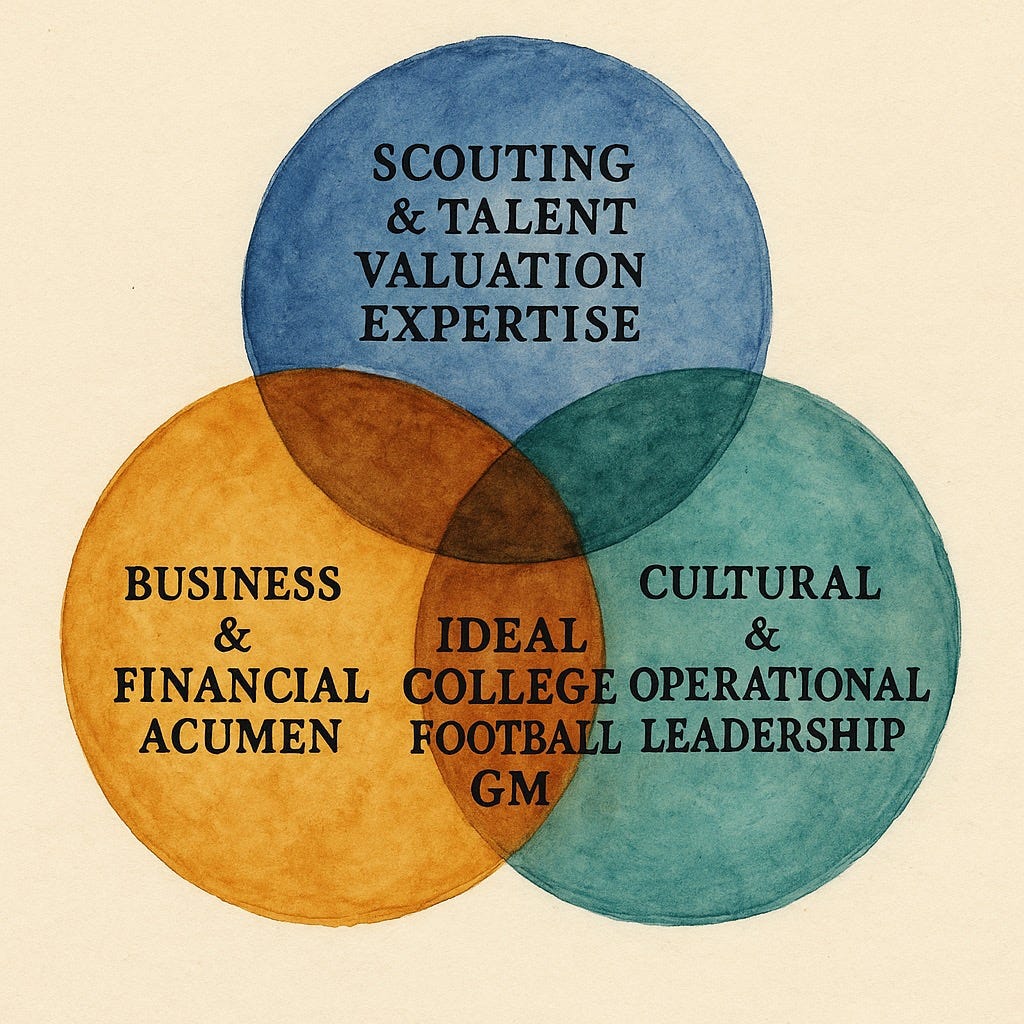

What a Proper “College GM” Should Look Like

If we apply economic logic — viewing the football programme as a portfolio of human capital assets, brand equity and media rights — the ideal GM hire can be defined across three dimensions:

A. Scouting & Talent Valuation Expertise

Someone who understands talent projection across high school, JUCO, and portal markets — i.e., what is the net present value (NPV) of a recruit vs a transfer?

Should be able to evaluate “cost-per-win” metrics and apply them to recruiting vs performance. For example, one study found the average cost-per-win (from 2014-18) was about US$3.54 million.

Must integrate analytics and film study to separate hype from value.

B. Business & Financial Acumen

Understanding of NIL economics, brand monetisation, and how to structure athlete-brand partnerships.

Ability to allocate budgets across recruiting, portal spending, athlete retention incentives, and facilities/brand enhancement.

Should treat athlete “investments” like assets with expected returns (on-field success, brand growth, alumni engagement).

Example: recent regulatory changes allow schools to share revenue with athletes (cap ~US$20.5 million in 2025-26).

C. Cultural & Operational Leadership

Must be credible with coaches, athletes, agents, boosters, and media — bridging the football operation and the business operation.

Should manage athlete lifecycle: from recruitment, development, brand growth, transfer/exit strategy.

Should design systems (data dashboards, ROI tracking, brand metrics) rather than leave everything to custom, ad-hoc coach workflows.

Why Schools Are Still Missing the Boat

Hiring on name / brand: Too many programmes hire ex-stars or media personalities to head player-development or “athlete experience” roles under the guise of “GM,” but these often lack business discipline or scouting depth.

Coach-centric governance: Athletic departments still default to the head coach as the de facto GM, thus limiting the strategic separation of duties.

Underinvestment in infrastructure: Data show budgets are high, but many of those budgets go to facilities and coaches’ salaries — less to front-office analytics, NIL strategy, roster engineering.

Inertia and culture: College athletic departments may undervalue the shift from amateur model to enterprise model. Institutional resistance means the functional change lags the economic change.

Mis-alignment of incentives: Without a GM, incentives remain aligned to short-term wins rather than long-term asset management. The coach wants wins now; the program needs sustainable value.

Strategic Implications for the Next Decade

Programs that hire a true GM — one with the three dimensions above — will likely reduce cost-per-win, improve athlete retention, improve NIL monetisation, and manage the transfer market proactively.

Those that ignore this shift will face rising costs, talent flight, weak donor signals, and growing gap between the haves and have-nots.

In the athlete labour market, games like recruiting and transfers will increasingly resemble business decisions rather than just moral-character judgments. The athlete will evaluate the programme not just on culture and coach but on brand value, transfer mobility, NIL upside, and opportunity cost.

For institutions, the football programme becomes less akin to a department and more akin to a subsidiary business unit — requiring CFO-level thinking, business models, brand value, and asset-management frameworks.

Conclusion

The data are clear: escalating costs, rapid mobility, athlete brand monetisation, and shifting competitive dynamics mean college football programmes are under a structural transformation. Yet many athletic departments continue to rely on outdated organisational models — expecting one coach to manage everything.

Programs that embrace the future by hiring a GM with scouting intelligence, business acumen, and operational leadership will gain competitive advantage. The ones that don’t will find themselves repeatedly chasing yesterday’s model with tomorrow’s economics.

In short: talent is capital, brand is leverage, and roster is portfolio. Treating it otherwise is no longer an option.